Recommendations and Supporting Findings

Our review of hundreds of studies and interviews with 38 cyber and industry experts revealed an echo chamber, loudly reverberating the enormity of the challenge and what needs to be done. (See our expert contributors in Appendix B.) The challenges the NIAC identifies here are well-known and reflected in study after study, including past NIAC studies, and recently in great detail by the Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity (CENC).

In this crowded space, the NIAC’s distinct value lies in its ability to provide insights from senior-level private sector owners and operators into how the government can best work with the private sector to secure the most critical infrastructure assets. Achieving the level of coordination required to act on these recommendations will not be easy. That is why several of our recommendations involve piloting innovative solutions with the most critical sectors, where urgency is high and senior leadership are already being engaged.

We have studied the cybersecurity challenge in detail and are ready to take action. Our 11 recommendations reflect a strong consensus on what must be done next. (Appendices C and D provide additional background, and Appendix E lists references.)

Recommendation 1

Establish SEPARATE, SECURE COMMUNICATIONS NETWORKS specifically designated for the most critical cyber networks, including “dark fiber” networks for critical control system traffic and reserved spectrum for backup communications during emergencies.

A Launch a pilot project to identify existing but unused/underused fiber networks (“dark fiber”) that could be used to create a dedicated communication network for critical infrastructure sectors. Demonstrate the ability for pilot organizations to operate critical control systems in isolation from public networks, making them more difficult to access.

B Identify and dedicate a secure backup communication system to enable real-time communication during a major, cross-sector cyber attack. This communication system may reserve a portion of the electromagnetic spectrum to separate it from any Internet or cyber-based communication network. It should enable, for example, electric utilities to communicate with utility crews working in the field to manually restore power after an attack.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), National Security Council (NSC), and the Strategic Infrastructure Coordinating Council (SICC) (Electricity, Financial Services, and Communications Sectors)

Supporting Findings

The scale, scope, and frequency of cyber attacks on digital and physical infrastructure systems is growing rapidly. Threats are escalating as more sophisticated and organized attackers are designing targeted attacks to damage or disrupt vital services and critical physical systems.

- Cyber threats today are two-fold: attacks targeting information technology (IT), which includes the software and networks that underpin business functions in critical sectors like Financial Services, and attacks targeting operational technology (OT), which includes control systems designed to operate physical processes like power flows in the electric grid.

Industrial control systems connected to business IT systems and the Internet constitute a systemic cyber risk among critical infrastructure. Cyber-connected OT systems improve automation and efficiency in the control of critical processes—such as generation, processing, and delivery of power, water, fuel, and chemicals—but also introduce new cyber risks.

- Several power companies are moving their operational systems to dedicated, closed networks they own, rather than shared lines they lease from communication providers. Isolating these networks can significantly limit access points, giving operators fewer digital gates to guard.

Backup networks will quickly become flooded and unreliable in a major cyber attack that disrupts primary communications (Internet, email, phone, and cell communications). The government can dedicate spectrum for critical infrastructure communications to hasten response and recovery.

Recommendation 2

FACILITATE A PRIVATE-SECTOR-LED PILOT OF MACHINE-TOMACHINE INFORMATION SHARING TECHNOLOGIES, led by the Electricity and Financial Services Sectors, to test public-private and companyto-company information sharing of cyber threats at network speed.

A Use the pilot to identify and evaluate state-of-the-art technologies and software platforms, resolve interoperability issues, address privacy concerns, and work through legal and liability barriers that hamper or limit company-to-company and government-to-company sharing today.

B Leverage, build upon, and coordinate across existing platforms designed for rapid publicprivate sharing of cyber threats and attack indicators, including:

The Cybersecurity Risk Information Sharing Program (CRISP), operated by the Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center (E-ISAC), which uses classified analysis of network traffic to identify attacks.

The Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center’s (FS-ISAC) machine-tomachine information sharing programs, now also used by some in the Energy Sector.

DHS’s Automated Indicator Sharing (AIS) platform, which releases attack indicators from multiple sources.

C Use lessons learned to identify platforms, protocols, and best practices that Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) can use to expand the pilot to other critical sectors, and guide machine-to-machine research and development (R&D) as appropriate.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: DOE, DHS, ODNI, NSC, and the SICC

Supporting Findings:

The public and private sectors remain unable to move actionable information to the right people at the speed required by cyber threats. Threat information and mitigations must move at network speed. Advances in machine-to-machine information sharing and automated mitigations show great promise.

Machine-to-machine information sharing technology and processes are still immature, and must grapple with significant legal, liability, technology, trust, and cost challenges. A pilot offers the opportunity to coordinate on key issues:

Securely sharing real-time system data with the federal government requires significant trust regarding how the information will be protected, shared, and used. Leaked data creates significant business risks and liability protections are not court-tested.

Machine-to-machine sharing requires consensus on common technologies, data formats, protocols, and policies.

Automatically implementing mitigations can create unpredictable outcomes in operational control environments.

Automated indicator sharing can overwhelm operators with data, making it difficult to parse and prioritize.

The most effective, value-added platforms will incorporate public-private and business-tobusiness information exchange.

The private sector has more raw, real-time network data of value, and sharing information between companies is often faster.

Government analysis adds value by connecting the dots across companies to reveal potential threats, add intelligence insights, understand intent, and provide warnings. Today, the time required to vet, analyze, and obtain permission to share threats creates significant delays.

Businesses can best lead the development of trusted solutions that meet their needs.

ISACs vary dramatically in effectiveness across sectors based on their organization, industry trust and buy-in, member retention and growth, and level of resources. But ISACs serve as a critical conduit for threat information from the Intelligence Community and for company-to-company exchange. Highly functioning ISACs should be used as a model for other sectors.

Recommendation 3

Identify best-in-class SCANNING TOOLS AND ASSESSMENT PRACTICES, and work with owners and operators of the most critical networks to scan and sanitize their systems on a voluntary basis.

A Develop a voluntary, cost-shared scanning and assessment program that provides onsite tools and expertise to help organizations: 1) test their systems for malware using best-in-class tools, 2) sanitize their systems, and 3) identify government and industry tools and service providers to upgrade and maintain system security.

B Establish a Center of Excellence to showcase best-in-class tools across government and industry and provide a test bed environment for companies to test and evaluate new software, particularly for use by small and medium-sized companies; and recognize, use, and expand cybersecurity programs at existing educational institutions.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: NSC and DHS

Supporting Findings

Managers often do not fully understand the magnitude or complexity of the risks they face, or to what extent their systems may be compromised.

Security researchers report that more than 30 percent of computers worldwide likely have some malicious code or malware, but few companies understand the extent of potential breaches.

As a result, many companies are not practicing basic cyber hygiene despite the availability of effective tools and practices. There is a broad lack of awareness of the federal tools available to help scan, detect, mitigate, and defend against cyber threats.

The owners of critical systems can range from Fortune 100 companies to small businesses, with diverse risks, resources, and cybersecurity needs. Customizable solutions are needed, and one-sizefits-all tools are rarely effective.

- Government tools or capabilities are often most useful to entities with lower levels of cybersecurity maturity or during widespread cyber attack.

Supply chain risks remain a struggle for system operators, who lack a trusted method to verify the provenance and custody of digital components from design and manufacture to integration and use.

- There is no way to test for embedded threats or verify the security of devices for critical OT systems. DOE, the National Labs, and DHS could work with the electricity industry and component manufacturers to develop an industry-driven method to verify and certify supply chain security for OT system devices.

Recommendation 4

Strengthen the capabilities of TODAY’S CYBER WORKFORCE by sponsoring a public-private expert exchange program.

A Implement a public-private sector employee exchange program to provide federal employees with a better understanding of the day-to-day operations of critical infrastructure and the role of cyber systems. This could help the federal government better identify and design programs, tools, and resources that can assist private sector organizations and overcome barriers to their use. For private sector employees, the program would provide a better awareness of the programs, tools, and resources available from the federal government. In addition, cross-training federal contractors who have appropriate clearances on industry control systems can also enable a stronger response to cyber attack.

B Prioritize federal and congressional action to expand cyber workforce programs, using the findings of the review required in EO 13800 to build a sustainable pipeline and address the expected shortfall in qualified cyber personnel.

Congress should also consider expanding scholarship-for-service programs focused on attracting the next-generation cyber workforce.

Sponsor clearances for students in college-level cybersecurity programs to speed access to qualified cyber personnel and encourage valuable internship programs.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: NSC, DHS, and Congress

Supporting Findings

The public and private sectors must compete for a limited pool of highly trained cyber experts, creating a shortage of cybersecurity leadership and expertise. The shortfall of qualified cyber experts is forecasted to reach 1.8 million unfilled positions by 2022.1

- The federal government’s numerous cyber workforce development programs are now being reviewed under EO 13800, and near-term action on the recommendations should be a priority of the Administration. (See Appendix C for detail.)

Federal cyber experts have a limited understanding of unique private sector systems, which limits their ability to provide technical assistance, particularly in response to a cyber attack. A focused effort is needed to develop both cyber expertise and operational system expertise across industry and government.

1Center for Cyber Safety and Education. Global Information Security Workforce Study. 2017.

Recommendation 5

Establish a set of LIMITED TIME, OUTCOME-BASED MARKET INCENTIVES that encourage owners and operators to upgrade cyber infrastructure, invest in state-of-the-art technologies, and meet industry standards or best practices.

A Incentives could include regulatory relief from frequent audits, reporting, and self-reports when industry standards are routinely met; a limited-time tax credit to incentivize security system upgrades; or grant and investment programs to fund upgrades or security investments without requiring a rate-based modification.

B Require implementation of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework to qualify for incentives for the most critical assets, and recognize that small and medium-sized businesses will need additional support to meet the requirements.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: DOE, DHS, ODNI, NSC, Congress, and the SICC

Supporting Findings

Cyber regulations are often blunt tools that are unable to keep up with dynamic risks in an arena where attack and defense capabilities change rapidly over months and years, not decades.

Prescriptive requirements result in a focus on compliance rather than maintaining best-inclass security. However, many experts noted that regulations are an effective government tool to drive a minimum level of cyber hygiene.

Outcome-based requirements give companies the flexibility to best achieve or exceed objectives, while allowing for variations in company structure, size, and resources.

Outcome-based market incentives can encourage large-scale infrastructure upgrades, directing company resources toward exceptional security rather than demonstrated compliance with minimum standards.

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework is viewed as a foundational document for providing guidance and identifying the minimum best practices for cybersecurity.

Recommendation 6

Streamline and significantly expedite the SECURITY CLEARANCE PROCESS for owners of the nation’s most critical cyber assets, and expedite the siting, availability, and access of Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (SCIFs) to ensure cleared owners and operators can access secure facilities within one hour of a major threat or incident.

A Direct agencies to facilitate and prioritize Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information (TS-SCI) clearances for at least two key personnel at every organization operating the nation’s most critical cyber assets (for which an attack could result in catastrophic effects to public safety, economic, or national security).

B Improve the transfer of clearances: require clearances sponsored by any agency to be accepted by all other agencies, and facilitate the transfer of clearance sponsorship as individuals move among agencies and to the private sector.

C Expand the number of SCIFs nationwide, and ensure secure information can be shared simultaneously between SCIFs maintained by different agencies.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: DHS, ODNI, NSC, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM), and all agencies that issue/sponsor clearances

Supporting Findings

Despite dedicated private sector clearance programs, too few of the right individuals in private companies have clearances at the right level to receive timely cyber threat information and act on it. Critical businesses need, at minimum, two cleared individuals to respond to potential threats.

The federal clearance process is time-consuming, inefficient, and difficult for the private sector to navigate. Clearances can take more than a year to process.

Federal agencies do not easily transfer clearances or universally reciprocate clearances issued by other agencies. Individuals must frequently restart the lengthy clearance process.

Clearances appear to be position-specific and do not move with the individual. Individuals who hold a clearance with one agency and move to another role, or move from the federal government to private sector employment, often cannot transfer their clearance to the new agency that must sponsor it, and must often restart the entire clearance process from the beginning.

This is inefficient, duplicative, and prevents previously cleared employees from acting to improve the cybersecurity of critical companies.

Clearances have limited value if private sector individuals cannot rapidly access secure facilities to receive sensitive intelligence on cyber threats. Private sector personnel may have to travel more than an hour away to access SCIFs, or even fly to DC to attend in-person briefings. A fast-moving cyber incident will not allow time to share information at this speed.

Recommendation 7

Establish clear protocols to RAPIDLY DECLASSIFY CYBER THREAT INFORMATION and proactively share it with owners and operators of critical infrastructure, whose actions may provide the nation’s front line of defense against major cyber attacks.

A Engage and embed cleared private sector representatives from the most critical infrastructure assets in government intelligence and information sharing centers to help inform and prioritize information declassification. Industry generally needs to know when, how, and what to protect from attack—not who might launch an attack or why

Examine the Kansas Intelligence Fusion Center as a model for co-location and information sharing. This fusion center has private sector representatives cleared to the TS-SCI level who are actively working on cyber issues side-by-side with the National Guard and other agency representatives.

Consider significantly expanding the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC), which provides a central location to coordinate public-private information sharing and response, and increasing ISAC integration.

B Expand the mission of intelligence agencies to proactively share intelligence with private sector owners and operators to support the defense of critical civilian infrastructure. Establish protocols that require intelligence analysts and federal response officials to rapidly share threat vectors and attack indicators—either with cleared individuals or through declassification—as early as possible.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: NSC, DHS, ODNI, FBI, and the Intelligence Community

Supporting Findings

The inability to rapidly declassify and share the less-sensitive elements of a potential threat, like threat indicators or vulnerabilities, leaves private companies in the dark for too long.

Those with a high need to know—businesses who could immediately act to secure critical systems—are often some of the last to know.

Our processes to share classified intelligence were designed for slower-paced threats and are insufficient as cyber threats escalate.

Intelligence agencies do not have the clear mission or processes to proactively declassify information as a threat unfolds, as they have not historically needed to treat private businesses as primary customers of threat data.

- Intelligence agencies have the authority to declassify and share information, but often lack the clear mission. While DHS has a clear mission to share with the private sector, it often does not “own” the information and must work through other agencies to declassify and share.

Building trusted relationships is at the core of effective information sharing. Agencies and businesses must work as trusted partners in securing the nation from cyber threats and work proactively to understand operational and information needs.

Recommendation 8

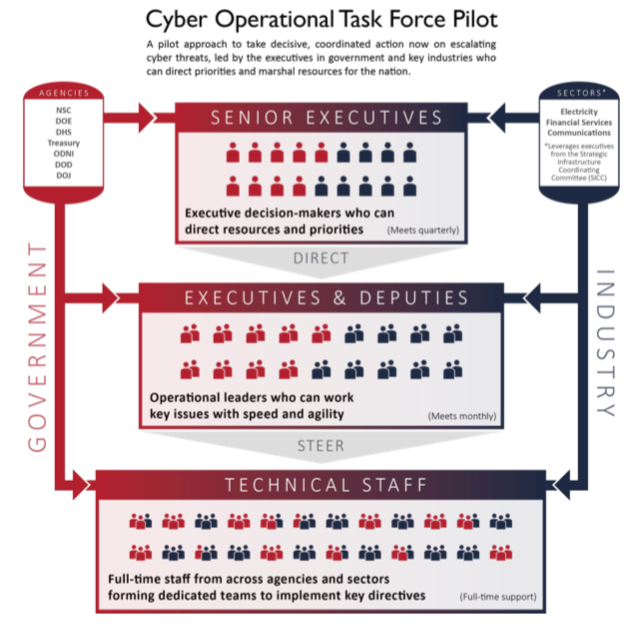

PILOT AN OPERATIONAL TASK FORCE OF EXPERTS IN GOVERNMENT AND THE ELECTRICITY, FINANCE, AND COMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRIES—led by the executives who can direct priorities and marshal resources—to take decisive action on the nation’s top cyber needs with the speed and agility required by escalating cyber threats.

A Establish a three-tiered task force that includes: 1) senior executives in industry and government with the authority to set priorities and direct resources, 2) operational leaders who work the issues and implement strategic direction, and 3) dedicated full-time operational staff from both industry and government that dig in and solve complex issues. This operational component is crucial if the task force is to be successful.

B Leverage the SICC to identify executives in the Electricity, Financial Services, and Communications sectors willing to participate in the pilot task force.

C Use the NIAC’s recommendations and findings as a starter agenda to provide critical areas for focus. The task force should tackle persistent barriers to cyber coordination and information sharing, such as legal and liability issues, data privacy concerns, fragmentation of authorities, and cost allocation for improving the security of private networks.

D Use lessons learned and best practices from this pilot to expand the task force coordination approach to other sectors and assets.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: DOE, DHS, ODNI, NSC, the SICC, DOD, U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury), and U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ)

Recommendation 8 pilots an approach for agile, integrated action that we believe will be pivotal to achieving the level of coordination required to act on all recommendations. The graphic below illustrates how this pilot could be implemented.

Supporting Findings

- **Today’s fragmentation of federal cybersecurity capabilities, authorities, missions, roles, and oversight is inefficient and precarious.** A bold new approach is needed.

- **Solutions to intractable cyber issues cannot be designed or led by any one agency**. The NIAC identified persistent, foundational coordination issues that will require a challenging reexamination of how agency missions are aligned and authorities are applied. Executive leadership and direction is required.

- **Key stakeholders in the Administration must champion cybersecurity with the private sector.** We need senior leaders to converge on national priorities, establish a clear agenda, and direct an operational team of cross-agency, public-private staff to triage and make headway on the biggest needs.

- The operational task force would not be another advisory council or other passive coordination group. It is intended to design and *implement* solutions.

- **Senior-executives are crucial to driving action** because of their ability to set strategic direction and priorities, apply resources, and exercise accountability.

- **A pilot task force with the sectors facing the most urgent threats** and that have high executive engagement (i.e., Electricity, Financial Services, and Communications Sectors) will be able to mobilize quickly, tackle the most pressing issues, and allow the format to be tested to determine if it can be applied more broadly across sectors.

- Senior executives in the Electricity, Financial Services, and Communications Sectors have formed the SICC to serve as a focal point for government engagement and cross-sector coordination.

Recommendation 9

USE THE NATIONAL-LEVEL GRIDEX IV EXERCISE (NOVEMBER 2017) TO TEST the detailed execution of federal authorities and capabilities during a cyber incident, and identify and assign agency-specific recommendations to coordinate and clarify the federal government’s response actions where they are unclear.

A Invite executives and representatives from the Financial Services and Communications sectors to participate in exercise planning, ownership, and execution.

B Require key agencies to develop white papers in advance of the exercise that outline specifically how federal authorities will be executed in extreme situations to support response. Use the National Cyber Incident Response Plan (NCIRP), which outlines roles and responsibilities, and identify potential gaps in processes and protocols.

C Test federal decision-making, protocols, and procedures as it exercises specific authorities and capabilities during the exercise. For example, DHS has conducted extensive research into how to apply the Defense Production Act during an incident to prioritize resource allocation.

D Use the exercise to further validate and refine the results of the DOE, DHS, and ODNI assessment—called for in EO 13800—of the nation’s readiness for a prolonged power outage associated with a significant cyber incident.

E Direct specific recommendations from the GridEx after-action report to specific agencies for implementation. The Administration should support and provide resources for agencies to implement the recommendations.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: DOE, DHS, ODNI, NSC, and the SICC

Supporting Findings

Our response to a large-scale, cyber attack with physical consequences on critical infrastructure today is likely to be insufficient. High-level federal cyber incident response authorities are clear, but the specific timing, processes, and coordination of resources is not well understood by federal personnel or industry owners and operators.

Several agencies have substantial emergency authorities during a major cyber attack, but it remains unclear what triggers those authorities, how they are applied, who authorizes them, and when.

High-level cyber incident response roles are defined in the NCIRP, but it remains unclear what triggers federal assistance and what it will look like in practice.

The timing and resource needs for a cyber incident will be largely different than for physical disaster response. Detailed policies, procedures, and federal technical assistance, and mutual assistance agreements must be developed and exercised. Gaps and issues must be addressed in coordination.

Recommendation 10

Establish an OPTIMUM CYBERSECURITY GOVERNANCE APPROACH to direct and coordinate the cyber defense of the nation, aligning resources and marshaling expertise from across federal agencies.

A Use the cyber task force (see Recommendation #8) to evaluate effective cyber governance models from other nations and recommend the best approach to centralize and elevate cyber governance and enable national-level coordination for public-private cyber defense. Although the circumstances in the United States are different than in those nations, we believe that better coordination at the senior levels of the U.S. government would improve operational control over individual federal elements and help ensure an effective response to the cyber threat.

B Consider establishing a senior-level position or similar unit that can effectively coordinate and exercise operational control over individual federal organizations. This may require congressional action and broad public recognition of the urgency of the cyber threat—which experience shows may not come until after a catastrophic cyber incident occurs.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: DHS, ODNI, NSC, DOJ, DOD, and Congress

Supporting Findings

The substantial capabilities among federal agencies are collectively insufficient to address sophisticated cyber threats because they are divided, uncoordinated, and often duplicative.

There is a large amount of dedicated, mission-oriented work being done by individual agencies. There are 6 federal cybersecurity centers, 140 cyber authorities and capabilities across 20 agencies, 4 tools, and 8 assessment programs.

This is indicative of both the enormous complexity of the problem and the fact that there are not and cannot be silver-bullet solutions.

Existing structures and legislative authorities result in numerous agencies and dozens of Congressional committees with cybersecurity oversight, yet limited national-level consensus on priorities for focused action.

Innovative national governance models for cybersecurity show that effective coordination, at speed, is driven by a central authority that can coordinate cyber priorities for the nation, align industry and government resources, and provide national leadership for cyber defense. (Appendix D summarizes new governance models recently unveiled by Israel and the United Kingdom.)

Recommendation 11

Task the Homeland Security Advisor to review the recommendations included in this report and within six months CONVENE A MEETING OF SENIOR GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS to address barriers to implementation and identify immediate next steps to move forward.

A In 12 months, task the NIAC with tracking the status of implementing these recommendations to create a focused and planned opportunity to measure our progress to improving cybersecurity of the nation’s most critical infrastructure assets.

ACTION REQUIRED BY: Homeland Security Advisor

Supporting Findings

There is an urgent need to act. Major attacks and watershed incidents—like the 9/11 attacks—have historically triggered a new level of strategic, coordinated action driven by public demand and strong political will. We have an opportunity to demonstrate foresight and leadership before a cyber attack severely disrupts critical services.

We believe a senior Administration official like the Homeland Security Advisor can provide the authority and leadership to convene heads of government agencies and lead a rapid advancement in the nation’s cyber capabilities with industry leaders.