- 6. FINDINGS

- 6.1. Examine the Impact of a Cyber Event on Army Force Projection

- 6.2. Exercise the Cities of Charleston and Savannah in Cyber Incident Response

- 6.3. Reinforce a Whole-of-Community Approach

- 6.4. Examine the Coordination Process for Providing Cyber Protection Capabilities in Support of DSCA

- 6.5. Support the Development of an Adaptable and Repeatable Framework

- 6.6. Recommendations

- 6.6.1. Municipalities should consider adopting new internal incident command structures that enable the formation of tailored whole-of-community efforts consisting of synchronized communication, information sharing, and resource allocation during cyber and emergency incident response.

- 6.6.2. Establish a mentorship program between municipalities that encourages information sharing and joint cybersecurity exercises. The partnership program provides a safe learning environment in which local organizations can further develop their working relationships.

- 6.6.3. Federal, state, and local leaders must recognize cybersecurity and cyber incident response as a key responsibility and allocate resources to personnel, training, and education shortfalls accordingly.

- 6.6.4 State cyber and emergency incident response entities, such as the SC Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity (SC CIC) program within SLED and the Georgia Emergency Management and Homeland Security Agency (GEMA), should work to establish standing, mutually supportive cyber resource support agreements that utiltize the Emergency Management Assistance Compact framework and Mission Ready Packages to build regionally focused cyber incident response and support plans for responding to a cascading cyber incident.34

- 6.6.5. Federal and state entities should execute annual law and policy TTXs that extend to municipalities and private industry. These events provide a venue in which leaders and responders can identify gaps in authorities, rehearse resource requests, and identify potential thresholds. In particular, State and National Guard response authorities and mechanisms differ by state and locality, and these will continue to evolve as cyberspace is better understood. As such, the law and policy TTXs will be critical for understanding the roles and responsibilities associated with utilizing National Guard resources.

- 6.6.6. Federal and state agencies should design and establish a data repository for resources and data related to cyber incidents, tailored responses, impacts, and exercises to facilitate the sharing of policies, procedures, best practices, data, and emerging issues. The repository should be open for municipalities and private entities to deposit and utilize resources to increase the resilience of their associated critical infrastructure.

- 6.6.7. DHS, in concert with the DoD, should examine and potentially expand the United States Coast Guard Cyber Command’s (CGCYBER’s) authorizations, resources, and mission set to include initial cyber incident response support for strategic ports and port cities.

- 6.6.8. Through the respective garrisons, U.S. Army Installation Management Command should work to develop, incorporate, resource, and exercise a tailored cyber incident response annex within its emergency incident response plans for force projection and deployment operations.

- 6.6.9. DoD planners must utilize integrated campaigning at multiple echelons (city, county, and state) to understand adversary actions against interorganizational partners and better inform campaign plan assumptions.

- 6.6.10. In conjunction with academic and government partners, the ACI should develop and implement automated tools that will allow novice planners to rapidly design and quickly execute JV-like events.

- Table of Contents

6. FINDINGS

6.1. Examine the Impact of a Cyber Event on Army Force Projection

Though scenario injects focused on roadway congestion, rail delays, physical security considerations, communication with local authorities, and direction from higher headquarters for redirecting cargo, JV 3.0 illustrated how a cascading set of “below the threshold of armed conflict” events could disrupt local transportation unit operations involving these sectors. The effects of concurrent emergencies and cyberattacks on critical infrastructure owned by municipal, state, and private sector organizations could create conditions that cause force deployment and projection operations to halt, introducing a crucial decision point about whether to close the port or potentially divert deploying unit personnel and equipment elsewhere.

6.1.1. Findings

- 1.The Army relies on various interdependent critical infrastructures, the majority of which it does not own or operate, making its domestic operations heavily reliant on external resources.

Figure 8: All Hazards Analysis (AHA) Dependency Model for the Transportation Sector—North Charleston

Figure 9: All Hazards Analysis (AHA) Dependency Model for the Transportation Sector—Savannah

a. Army transportation units responsible for moving, deploying, and sustaining combat power are reliant on both public and private critical infrastructure sectors, including energy (power), transportation (ports, rail, and road), and communications, that together enable the success of the units’ mission. The interdependencies between these different sectors has the potential to create a set of complex and unanticipated challenges for these units and their mission. Figures 8 (North Charleston) and 9 (Savannah) show the All Hazards Analysis (AHA) dependency models for the transportation sector (see appendix H). In both figures, we see how electricity (red points and lines), natural gas (yellow points and lines), water (blue and light-blue points and lines), and communications (orange points) support and interact with port facilities (black points) and the rail network (orange lines). The JV 3.0 exercise showed how cyber or physical events that impact a single sector can generate cascading effects across interdependencies and introduce unplanned decision points for unit leaders.

b. Each port authority determines access to terminals and works with the United States Coast Guard (USCG) to determine the extent to which the port remains in operation, depending on the type and severity of incidents. In both the Charleston and Savannah events, the captains of the ports closed the ports pending the investigation of issues and the cleanup of cargo containers being dumped into the channel.

c. Rail companies have the final say in determining alternate routes for cargo in the event of redirection or recontracting. Trucking companies are another option for the movement of cargo, but the number of available drivers required to move a significant number of containers may exceed the capacity available locally.

d. Both ports and the surrounding areas use all forms of major commercial transportation to move to and from the port. Though this event included trucking and rail, it did not discuss the role of surrounding airports in movement to and from the ports.

- 2. A sophisticated adversary can disrupt force deployment and cause units to miss the Required Delivery Date (RDD) by targeting commercially owned critical infrastructure and local municipal sectors.

a. During the scenario, the movement of military equipment was disrupted by a combination of traffic delays; social media-incited protests; port access manipulation; the manipulation of rail and vessel cargo manifests; natural gas and electrical disruptions; and, ultimately, interference with the weight distribution for the automated load plan for a ship in port, causing it to tip and dump containers into the channel.

b. The only military infrastructure directly targeted in the scenario was SDDC email accounts. However, there was no significant escalation resulting in apparent disruptions that would cause excessive resource allocation. The Emotet malware’s automated propagation caused this compromise, but there was virtually no conversation about this particular thread, and it was never intended to be a primary concern.

c. In the scenario, a brigade-sized armored task force consisting of approximately 2,300 pieces of equipment was tasked to conduct a rapid deployment to a theater of operation. Using the movement from Defender 2020 as a template for the JV 3.0 scenario, the movement of this equipment to the port would require four trains with 50 cars apiece, 100 to 150 trucks, and 20 serials of military convoys. As a result of cyber incidents during the scenario, approximately 280 pieces would have been delayed or stopped upon the closure of the port at the end of turn 5:

i. Two trains with 120 pieces of cargo, with the possibility of delaying or stopping two more trains;

ii. Twenty to 40 trucks with 100 total pieces of cargo; and

iii. One serial of a military convoy with 60 pieces of cargo, with the possibility of delaying more.

d. The ACI and its partners developed a Monte Carlo simulation to analyze potential alternatives for the commander (details on the simulation are found in appendix J):

i. Remain at the original port until it remediates physical and cyber issues (at the end of turn 5, a cargo ship listed and dumped containers into the channel);

ii. Assume there are no issues with the channel and remain at the original port until it remediates the cyber issues;

iii. Relocate to a new port 200 miles away; and

iv. Relocate to a new port 1,000 miles away.

e. The goal of the simulation is to generate a distribution that represents the number of days required to complete the force projection operation, and then develop probabilities associated with successfully making the original RDD of June 1, 2020 (complete movement in 28 days or less). For the alternatives analyzed, remaining at the original port provides commanders the best probability of arriving by the original RDD (23-percent chance of successful completion in 28 days when required to clear the channel and 77-percent chance of successful completion when there are no issues with the channel). Even with a significant physical effect (blocked channel), the alternatives that involved moving showed much less promise. For these alternatives, the time is dominated by recontracting and replanning for the new port (moving to a new port 200 miles away has a 1-percent chance of successfully making RDD). Appendix J provides more information on the simulation.

- 3. A sophisticated adversary can disrupt deployment and cause units to miss the RDD by using cyber capabilities that do not trigger an armed response but still achieve cascading effects that complicate a coordinated response.

a. No one scenario event seemed challenging enough to prevent a force projection operation from achieving its RDD. These delays, though, negatively impact the marshaling of space and load planning at the port of embarkation. Although it is possible to load vessels with equipment that has arrived at the port staging areas, the delays impact load planning (by both the military and contractors) that would likely decrease the operational capability and capacity of elements when they arrived in their designated theater of operations. Geographic combatant commanders and their subordinate task force commanders would likely require significant operational plan modifications to meet impending deadlines due to these force packages being disrupted at the port of origin and the intended port of debarkation. The decision to ultimately divert equipment and personnel to an alternate port of embarkation creates additional timing concerns regarding expected arrival times within a theater of operation; these concerns include, but are not limited to, convoy security, personnel availability, return, remarshaling, and departure to an alternate port.

b. The Emotet cyber tool was the chosen malware tool for the JV 3.0 scenario due to its availability and annual release since 2016.22 The Planning Team chose events for the scenario that mirrored real-world incidents in which it was unclear whether the actors were nation-state operatives.

c. Using inject distribution directed by DECIDE®, participants faced a situation with imperfect information. The deliberate nature of inject escalation allowed each sector to handle initial incidents with ready resources and known agreements. Soon, however, participants acknowledged service disruptions were leading to overwhelming downstream effects on other sectors. In both cities, once participants acknowledged that the scenario events were clearly indicating a coordinated cyberattack by an unknown adversary beyond their ability to manage, they shut down the ports indefinitely. The closing of the ports pushed SDDC to identify alternative means of force projection.

d. During execution, participants avoided discussion about attribution because it was not clear to them that the incidents had been caused by cyberattacks, much less a sophisticated adversary. By the time the players were willing to state that the set of incidents was a coordinated effort, the damage was extensive and attribution was highly unlikely.

- 4. Interactions and interdependencies between communications and information technology (IT) systems present new gray-zone attack vectors that can have debilitating impacts on Maritime Transportation System (MTS) operations vital to force projection.

a. The UIUC CIRI Port Disruptions Tool (PDT) simulation (see appendix I) used incidents consistent with the injects in JV 3.0 to demonstrate the potential impacts of fort-to-port, communicationbased disruptions on force projection.

- b. A train derailment due to compromised rail-control signals introduces a minimum 2-day disruption that requires significant coordination and reallocation of resources for mitigation and response (see disruption 1 [D1] in appendix I). The challenges associated with mitigation include the location of the derailment (more complex in an urban environment as opposed to a rural one), the impact of rerouting rail and road transportation movements, and the speed with which additional movement assets can be acquired. Furthermore, any change to the arrival schedule for the equipment will impact gate usage at the port as well as vessel loading.

22 Bromium, Emotet: A Technical Analysis of the Destructive, Polymorphic Malware (Cupertino, CA: Bromium, 2019); and “Alert (TA18- 201A): Emotet Malware,” United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team, updated January 23, 2020, https://us-cert.cisa.gov/ncas/alerts/TA18-201A.

c. The increased use of digital communications by railroad companies introduces the potential to delay rail by degrading the communication network (see disruption 2 [D2] in appendix I).23 In this situation, route choice may also affect the exposure of data to adversaries, depending upon the communications networks utilized. Exposure to unmanned aerial vehicle-based (UAV-based) man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks may be worse in rural areas, where railroad companies rely on wireless networks, and technologies may enable one to use MITM methods to access operational data via cell phone signals used by emerging applications employed by rail companies.

d. Rerouting traffic can result in new single points of failure across multiple critical infrastructure sectors (see disruption 3 [D3] in appendix I). Planners must recognize emerging risks due to the data or stakeholder dependencies of secondary and tertiary routes and time delays caused by disrupted movements.

- 5. The current multidomain environment becomes contested for deploying units as early as the fort, thereby presenting the potential for degraded freedom of maneuver when conducting home-station movement operations. Therefore, military deployment operations can no longer assume such favorable conditions and must plan and prepare for and be ready to mitigate such physical and cyber disruptions accordingly

a. Cascading cyber and physical incidents introduce several interrelated complexities that both local garrison commands and municipal emergency operations centers must be made aware of early due to mutual dependence on supporting critical infrastructure, such as energy (power), transportation (ports, rail, and road), and communications (telecommunication).

b. JV 3.0 exercise data highlights a gap in early indications and warning that leaves local garrisons unaware of initial cyber intrusion impacts across interdependent critical infrastructures. This observation further exposes the importance of:

i. Codified relationships between garrison emergency operations centers and civilian municipal entities;

ii. Established information sharing between emergency operations centers that communicate early and often when large ground convoys are traversing to or from ports of embarkation;

iii. Awareness of the availability of critical resources (and the entities from which these resources are available) to support mutual rerouting or cross-loading during such scenarios; and

iv. The establishment of multidomain protection protocols for all moving stock and associated personnel (military and civilian) transiting between installations and ports through mutually reinforcing agreements and relationships.

c. JV 3.0 interactions revealed that when responding to multiple events, garrison commands are continuously faced with taxing constraints that may divert critical resources and exceed maximum thresholds. This observation necessitates:

i. Designing, establishing, exercising, assessing, and codifying support structures among garrison, local, state, and regional emergency management, cyber incident response, and critical infrastructure partners.

ii. Establishing communication protocols among brigade, division, and garrison transportation offices along with SDDC, United States Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM), and municipal emergency service stakeholders when planning, preparing, and deploying unit convoys to and from ports of embarkation.

iii. Creating a common operating picture among local garrison, municipal, state, regional, and private sector partners with interdependent critical infrastructures to mitigate the disruption of departing convoys—a scenario that can present operational impacts across multiple domains.

23 Angela Cotey, “Railroad Communications Technology: From Cellular to Radio to Satellite to Wi-Fi,” Progressive Railroading, May 2012, https://www.progressiverailroading.com/norfolk_southern/article/Railroad-communications-technology-from-cellular-to-radio-tosatellite-to-Wi-Fi–30947.

d. Installation response plans, procedures, and protocols require additional development to ensure both a holistic response and the continuation of movement when garrisons are presented with emergency and cyber incidents that cascade across interdependent critical infrastructures. This observation further highlights:

i. The increasing feasibility and likelihood that garrisons will face a JV-type, complex, cyber and physical incident and not be structured, equipped, resourced, or prepared to adequately ensure sustained installation unit survivability and resilience.24

ii. The criticality of garrisons receiving early warning from both public and private sector partners at the first indication of a developing incident that has the potential to result in debilitating effects (both physical and digital) on deploying units.

iii. The importance of implementing an agile and flexible incident response framework that best enables continuous communication, cooperation, and collaboration among garrisons and municipal and private sector incident response stakeholders (both cyber and physical).

6.2. Exercise the Cities of Charleston and Savannah in Cyber Incident Response

Through JV 3.0, the ACI introduced a series of workshops and an exercise that allowed the cities of Charleston and Savannah to examine, assess, and update their current cyber incident response procedures. Although both cities’ capability to respond to natural disasters is very mature and wellrehearsed, incorporating a cyber element into the exercise provided an opportunity for the cities to rehearse their response plans; examine their protocols regarding cybersecurity; and improve communication within the cities, their departments, local critical infrastructure sectors, and regional organizations.

This was the first time that JV has looked beyond a single metropolitan area, exploring the similarities and differences between the laws, policies, and responses in two cities in the same region but different states. Originally intended to be conducted simultaneously and in parallel, COVID-19 forced the team to refocus efforts and conduct two identical scenarios one day apart. Both cities performed admirably through the planning process and exercise, with the research findings listed below.

6.2.1. Findings

1. There is no standard for cyber incident declaration. Cyber incident declaration was found to be insufficient in addressing activities that are rated as below catastrophic and are likely not as obvious, yet are still operationally impactful for all parties.

During the TTX, the ACI observed a general reluctance of participants to openly declare a cyber problem existed or state the circumstances unfolding could be, or were, connected to a cyber event. Although participants knew this was a TTX with a cyber nexus, the physical impacts of scenario events slowed the participants’ engagement in areas that could be cyber-related and the subsequent identification of indicators of potential emerging issues. Although many participants and entities had response plans that included cyber incidents, participants demonstrated more clarity on response, protocols, and processes when addressing elements of the exercise that were physical in nature.

24 Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Our Bases in US Will Be Attacked: Army,” Breaking Defense, December 14, 2020, https://breakingdefense.com/2020/12/our-bases-in-us-will-be-attacked-army/?fbclid=IwAR36rBTp-z55DAwDJM8seCsLT2ep0WeO7HCHl6NPnoOxctb70EsQpLkw9c, accessed January 5, 2021.

2. There is an emerging need for city-level information security departments to address potential cross-system issues between organic and isolated networks, such as supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) and traffic management systems.

Organization leaders should understand that information security and IT are separate disciplines and should allocate resources accordingly. The growing number, variation, and interconnectivity of municipal IT and operational technology (OT) systems, networks, and structures necessitates a deeper analysis of potential cross-system connectivity to be able to adequately address the potential impacts of a cascading intrusion that maintains the propensity for the degradation of multiple critical infrastructure sectors simultaneously due to shared connectivity, hardware, and/or software. This cross-system analysis should consider the following:

a. Review of all municipal agreements and contracts for the parameters of cyber incident response support from contracted vendors and firms;

b. Examination of municipal continuity of operations planning for city data facilities during a longterm degradation of critical infrastructure services, such as power;

c. Analysis of all upstream and downstream data transmissions to determine the potential for cascading impacts across multiple critical infrastructure sectors;

d. Risk analysis of municipal critical infrastructure systems that necessitate the sharing of common hardware and software;

e. Exploration of the potential for critical infrastructure system and network segregation when appropriate, feasible, and necessary to prevent widespread impacts of a cascading cyber incident;

f. Research on how critical systems (such as fire department mobile data terminals) might be impacted by a complete communications blackout; and

g. Analysis of how a complete communications blackout might affect municipal water and sewer resource networks, including SCADA and other critical systems.

3. Participants across sectors and levels of government noted that the realistic scenario incidents stressed the participants’ procedures and forced them to think differently.

Participants indicated through exercise survey responses that the presented scenario elements were realistic and comprehensively taxing for different sectors and entities and simulated the actual flow of an incident unfolding. Regarding scenario realism and the inducement of participant stress during the event, we asked participants to self-report stress levels after each turn. Accordingly, these data indicated that stress levels consistently increased from turn to turn as issues and challenges continued to cascade, with two-thirds of survey respondents indicating a high level of stress by the final turn of the exercise (see figure 10). This feedback indicates participants and their respective organizations felt enabled in implementing their respective incident response actions, and JV 3.0’s bottom-up approach was informative and added value to participants’ future decisions.

Figure 10: Stress of Participants by Turn

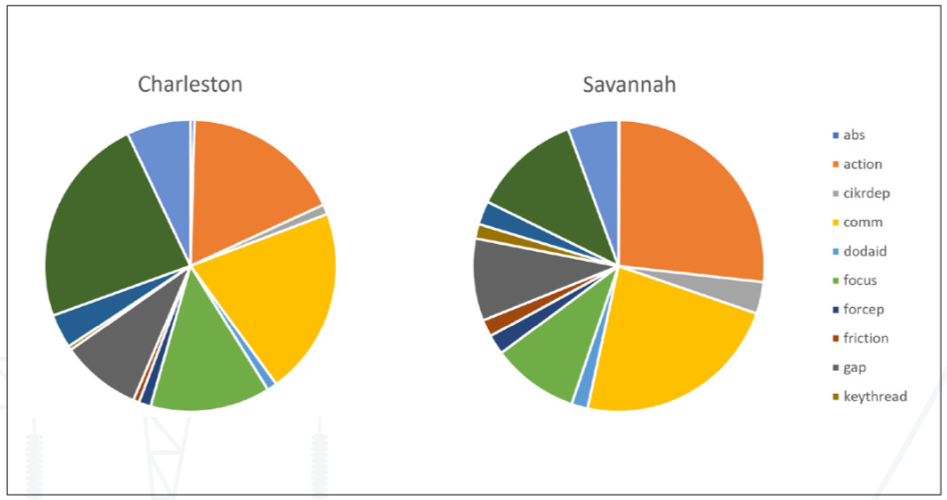

4. Participants across sectors and levels of government should use municipality-focused cyber exercises to improve overall incident response.

In both JV 3.0 exercises, participants overwhelmingly indicated with 88-percent positive responses that the exercise provided them with new information or sources of information relevant to incident response, such as available resources, new knowledge on infrastructure and policies, and organizations that support community lifelines. Eighty-four percent of survey respondents also reported that JV 3.0 helped them identify gaps in their respective incident response plans regarding knowledge, resources, communication channels, and the commitment of personnel during incident response. Additionally, 83 percent of survey respondents reported that participation in JV 3.0 would help their organization improve its incident response plan going forward. Figure 11 further illustrates this point, with a majority of participant-driven measures being classified as either a communication (orange), action (red), or plan (brown) between organizations throughout both iterations of the event. These response percentages, coupled with corresponding observation data and testimonials, suggest that most participants felt that their time, energy, and resource commitment translated into added value for their organizations following JV 3.0.

Figure 11: Participant-Driven Measures in the JV 3.0 Exercises

5. Municipality-focused cyber and emergency management exercises can be effectively executed in a distributed format that supports continuous participant engagement across both public and private sector stakeholders.

JV 3.0 demonstrated that it is possible to effectively conduct an event that exercises incident response in a distributed manner, utilizing multiple facilitation platforms. Participant survey responses and testimonials overwhelmingly support this finding, with 86 percent of survey respondents reporting that JV 3.0 held their attention and kept them actively engaged for most of the event. Individual testimonials further bolstered this finding, with one participant stating:

The Virtual means of delivery really shined [in including] everyone [as if they were] in one location. I believe that in an event of a real crises the need for IT system such as Decide in combination with MS TEAMS will really help facilitate communications, Corrective COA, and engagement from multiple personnel from multiple levels. I noticed everybody got to work simultaneously which I’ve never observed before.

The efficacy of this JV 3.0 distributed design also allowed additional entities, organizations, and individuals to participate that may not have otherwise had the ability to do so. Additional individual testimonials further reinforced this finding, with participants indicating that:

Doing this virtually actually helped me participate as I don’t know if I could have [gotten] away from the office to do this.

Great job for taking this virtual and still having this be a productive exercise.

This finding not only indicates the efficacy of this distributed iteration of JV 3.0, but also informs future research with respect to the creation of an automated JV platform in support of creating a repeatable and adaptable framework. The finding also suggests that there may be value in creating a virtual environment that supports multidomain collaboration when critical infrastructure organizations are managing cyber-physical incidents.

6.3. Reinforce a Whole-of-Community Approach

Whereas a whole-of-government approach is a culture that promotes information sharing, cooperation, and coordination of resources at all levels of government, the whole-of-community approach recognizes the physical and cyber interdependencies among all levels of government, private industry, and critical infrastructure sectors. Prior to the advent of cyberattacks, the United States could safely assume the civilian sector would operate smoothly in support of military and economic functions and its military dominance would protect domestic operations. Now, a clever adversary can use techniques and tools in cyberspace to exploit a host of seemingly minor interdependencies whose downstream effects will aggregate to a significant event.

There are relatively well-understood interdependencies among critical infrastructure sectors, such as natural gas and electric; power and water; and communications and ports, to name a few. To illustrate, figure 12 shows the AHA communication sector dependency model for major lifeline critical infrastructure (see appendix H). The upper-left quadrant shows communication dependency links (green lines) and communication facilities (orange circles), and the top-right quadrant adds nodes to indicate port facilities (black) and substations (red). The bottom-left quadrant shows the interdependencies that exist among electricity (red), rail (orange), natural gas (yellow), and water (blue). Given the multiple sectors included in the dependency model, it is imperative that local governments include as many critical infrastructure sectors in their cyber incident response plans, rehearsals, and exercises. Through the whole-of-community approach, we can identify where these interdependencies exist and take appropriate measures to ensure that incidents do not create cascading effects.

Figure 12: Communication Dependency Model (Charleston)

Perhaps most importantly, the local and private entities that are exploited to cause cascading effects are the first on the scene to combat the adversary. As such, initial response activities may be dictated by nongovernmental agencies. Whole-of-government culture for cyber incident response is good but insufficient; critical infrastructure resilience requires a culture that embraces and mobilizes the entire affected community.

6.3.1. Findings

- 1. Although traditional incident responses—such as for natural disasters or chemical or biological threats—are generally effective and coordinated, there is a need for improving responses to purposeful cyberattacks.

Cyber incident responses require rapid information sharing and requests for assistance from state and local players. Local events can have significant cascading impacts throughout the county, state, and Nation. Differences among city, state, federal, and private sector responses can add significant complexities. Thresholds for information sharing and reporting are critical to understanding situations and recognizing an attack. The exercise illustrated cases in which sharing and reporting did not happen in a timely manner or could not extend beyond an organization, thus preventing the early identification of a cyber incident. Also, gaps in understanding the chain of authority for requesting additional resources can impact requests for and the deployment of state and federal assistance.

Furthermore, differences among city, state, federal, and private sector incident responses and levels of transparency are not necessarily conducive to trust or situational awareness. Evidence from JV 3.0 clearly illustrates that different levels of government and different sectors have different perspectives, and each agency or level may only see part of the whole picture. After receiving the incident injects for each turn, the participants discussed the new or ongoing issues that were most relevant and pressing to their respective sectors; this information was tracked by data collectors using the data code “focus.” The word clouds in figure 13 illustrate that different tables (sectors) focused on different aspects of the situation. For example, the city table focused strongly on local traffic issues and, to a lesser extent, issues related to students (who were impacted by water supply issues at the schools). A key focus of the port table was a combination of power disruption issues related to protestors, continuity of operations, and potential impacts on the port’s military customers. The energy sector focused on responding to ransomware, maintaining its services for the business sector, and potentially leveraging third-party vendors to compensate for shortfalls. The federal/military sector reflected “cyber” as a front-and-center focus (though the word “ransomware” is in the word clouds for the other three sectors pictured).

Figure 13: These word clouds illustrate that different sectors had different perspectives, focused on different aspects of the situation, and allocated different weights to common issues.

2. JV 3.0 addressed the need of many participating agencies affiliated with the cities for fully formed response plans and communication networks. From a whole-of-community perspective, JV 3.0 demonstrated it is possible to bring critical public and private sector stakeholders together in the same exercise. Many exercises present notional injects that do not necessarily pertain to stakeholders’ organizations, sectors, or spans of responsibility. Though this approach helps maximize resources, it fails to bring the full complement of required participants to the table, a practice that distills interdependencies and gaps in cyber incident response. This need was identified by roughly half of survey respondents, who stated that they did not yet have a good awareness of how different organizations or sectors in their cities (and beyond) would communicate and coordinate during a cyber incident involving critical infrastructure. Although larger exercises come at a cost, participants desire to gain more situational awareness about the processes used across organizations. Some of the JV 3.0 participants’ expressed goals included the following:

a. “[To] better understand how the state and federal agencies work together for a non- [Department of Defense] cyber incident.”

b. b“[To achieve] better understanding of how state, local and commercial entities would respond in a crisis situation. At what point would this individual event be reported up to the Federal level.”

c. “[To] learn from other partners to gain knowledge on if and where . . . we fit into their plans.”

d. “[To] find out how to contact and utilize exterior assets during a cybersecurity attack.”

e. “[To] learn who I’d reach out to [outside of my organization] in the event of a cyber crisis.” Consequently, although a clearer understanding may exist at the state and federal levels, JV 3.0 highlights the desire for better understanding, knowledge, and integration at the municipal level—particularly, how to request assistance during cyber incident response.

3. JV 3.0 revealed the need for more regular and codified cross-sector communication and collaboration efforts during cyber incident response.

As mentioned earlier, JV 3.0 demonstrated an ability to bring stakeholders from various organizations and with different roles together under the auspices of a single cyber-physical critical infrastructure exercise. At the city level, there was a clear recognition of the need to conduct follow-on exercises that include multiple stakeholders to identify gaps in their cyber incident response plans, capabilities, and response actions across each community.

Communication network visualizations generated from the exercise data further illustrate the cross-sector collaboration efforts that were initiated during JV 3.0 due to various exercise elements being introduced within the scenario. Figure 14 is an illustration of scenario-induced cross-sector communication by exercise turn that took place during JV 3.0, with the port depicted as the center of gravity. Though the port is depicted as communicating with traditional maritime stakeholders, this visualization demonstrates increased coordination with new municipality, county, state, federal, and private sector stakeholders during response efforts as well.

Figure 14: In this snapshot visualization, the organizational nodes representing different agencies are sorted in clockwise order by the number of requests they made to another agency. The more requests the agency made, the darker the color. In addition, the larger the node, the more requests the agency received. The colors of the edges represent the turns in which the relationship occurred: orange for turn 4, green for turn 5, blue for turn 6, and purple for turn 7.

A municipality’s well-established and well-developed relationships with local stakeholders, both public and private, as well as effective internal communications and response actions are key strengths that can be leveraged during cyber incident response. Accordingly, JV 3.0 highlighted the value of further expanding cross-sector communications, plans, and cooperation, which can lead to earlier identification and consistent engagement with additional community partners—private industry, utilities, state entities, federal partners, and military installations—and thereby improve the speed, agility, and effectiveness of whole-of-community cyber incident response. Participant testimonials and survey responses underscore the importance of these scenario-induced cross-sector communications.

a. “Many issues were identified that were very relevant, especially in the areas of determining when agencies would actually talk to each other, and if we were even speaking the same language.” —City participant

- i. According to survey responses, scenario incidents prompted over half of participants (in both iterations) to contact (or want to contact) another organization at some point in the exercise, and approximately 20–30 percent of respondents signaled they reached out (or wanted to reach out) to an external organization during each turn of the event scenario.

4. JV 3.0 and the JV series continue to facilitate lasting relationships between a vast array of participating organizations, entities, and sectors

JV 3.0 planning, design, and execution afforded a multitude of participants various opportunities to interact, collaborate, and integrate cyber incident response efforts for the first time. Accordingly, participation in planning conferences, workshops, and mini-exercises (Law and Policy TTX / Jack Pandemus) enabled stakeholders to further codify and incorporate these new relationships in advance of event execution. This sentiment continued into event execution, with approximately 90 percent of survey respondents requesting that their contact information be shared with fellow participants to facilitate ongoing communication and coordination for postevent incident response. JV 3.0 brought numerous public, private, federal, and academic stakeholders together for the better part of 15 months, facilitating the creation of these vital relationships that remain critical to bolstering whole-of-community critical infrastructure resiliency when faced with cascading and cyber incident emergency situations.

5. JV 3.0 successfully brought together a wide array of public, private, military, and academic stakeholders during event planning, preparation, and execution for the first time. However, the consensus remains that these new relationships must be continually fostered, and additional stakeholders (those who did not participate in this iteration of JV) must be both identified and incorporated going forward through future, organically driven, JV-like efforts.

Municipal governments were the critical node for the JV bottom-up approach to increasing the resiliency of U.S. critical infrastructure. This iteration of JV continuously sought to facilitate a more robust whole-of-community response through the creation of new relationships, robust partnerships, and integrated joint response efforts. Although this was achieved to a great degree during JV 3.0 and fostered throughout its supporting events, efforts should be made to maintain these relationships while incorporating new and emerging stakeholders. This finding became clear when analyzing city-based communications following JV 3.0; it was evident that a concerted effort (driven by local communities) must be made going forward to continually strengthen and foster these new relationships, partnerships, and joint incident response efforts. Figure 15 is an illustration of emerging communication channels between the city and other important community stakeholders that began to take shape during JV 3.0. However, this graphic also depicts a need for further development, exercising, and codification of these new relationships not only with the participants that were present during this iteration, but also with additional stakeholders yet to be identified through future efforts that can continue to fill identified community gaps in resources, capabilities, and communication channels.

Figure 15: In this snapshot visualization, the organizational nodes representing different agencies are sorted in clockwise order by the number of requests they made to another agency. The more requests the agency made, the darker the color. In addition, the larger the node, the more requests the agency received. The colors of the edges represent the turns in which the relationship occurred: orange for turn 4, green for turn 5, blue for turn 6, and purple for turn 7.

6.4. Examine the Coordination Process for Providing Cyber Protection Capabilities in Support of DSCA

Based on the deputy secretary of defense’s Directive-Type Memorandum 17-007, Interim Policy and Guidance for Defense Support to Cyber Incident Response, 25 the ACI refers to Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) / Defense Support to Cyber Incident Response (DSCIR) to achieve effectiveness in coordinating responses to significant cyber incidents.

25 Robert O. Work, Interim Policy and Guidance for Defense Support to Cyber Incident Response, Directive-Type Memorandum 17-007 (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, updated May 29, 2020).

Though multiple agencies may be involved in the response, typically the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) or the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) operate as the federal lead agency for threat response activities. More specifically, the Department of Justice, acting through the FBI and the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force, is the federal lead agency for threat response activities; DHS, acting through the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center, is the federal lead agency for asset response activities; and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, through the Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center, is the federal lead agency for intelligence support and related activities.

6.4.1. Findings

- 1. Though DSCIR has been codified in policy, it has not yet been exercised, and it is unclear how it would work during an incident.

a. The Law and Policy TTX included a separate forum for federal, state, and local government representatives to discuss the process for local municipal and state governments to request support in the event of a cyber incident. The organizations that attended this and other workshops included both prospective requestors and providers. Prospective requestors did not know whom to contact or what the process for requesting assistance was, almost without exception, and were usually surprised when representatives from prospective providers identified themselves. Although JV allowed for these introductions, repeat examples underscore the division between those with resources and responsibilities to help and those who will need it when their own resources are overtaxed.

b. Many of the triggers for the release of resources are contingent on the declaration of a cyber incident, thereby delaying any possible DSCIR requests—assuming that participants know how to initiate them. When anomalistic behavior occurs, users tend to view it as a glitch or fluke and to attempt to restart or even replace systems. An adversary can exploit this by making cyber incidents ambiguous, increasing the time from discovery of the problem to cyber incident declaration.

c. In the event of a cyber incident at the municipality level, stakeholders would have to notify their respective states and/or the lead federal agency for the critical infrastructure sector involved. Once notified, the lead federal agency would be the entity responsible for requesting DoD support. Though the request process had happened multiple times, DSCIR support had not yet been executed by the Law and Policy TTX in February 2020. Two main drawbacks to DSCIR support are the time required to process the request and send support and the cost of support.

- 2. DSCIR should provide a menu of options and their associated costs similar to DSCA’s menu of physical assets.

a. JV showed that malicious actors can cause a series of minor disruptions and escalations that can cascade into a significant disaster. By overtaxing multiple local organizations (ranging from municipal to state) simultaneously, the aggregate effect created operational disruptions to force projection activities, but no organization was willing to declare it was being attacked, regardless of the perceived antagonist. In any case, the local emergency responders and private entities are likely to be the first to recognize malicious cyber activity if they are targeted; as such, they need the ability to immediately send situational updates to cyber response resources.

b. When the need for outside assistance becomes obvious, organizations are unsure what support to ask for because they are unsure of the resources that are available. For example, specialty software breaches, such as maritime software packages, require a different skill set than a Windows breach does. When requesting assistance, municipalities and critical infrastructure sector owners must provide details on what was breached, and they need to know if there are any federal assets available that are trained to assist with the technical challenges of the particular breach.

c. According to Directive-Type Memorandum 17-007, the procedures for reimbursing the DoD for DSCIR are found in DoD 7000.14-R, volume 11A, chapter 3.26 There are worksheets for determining the personnel costs, yet most still use language and costs associated with physical events and DSCA. The mechanisms and costs associated with requests for DSCA are well established, but the same is not true for DSCIR.

- 3. Whether DSCA or DSCIR is the appropriate mechanism for receiving support in the event of a cyber incident that is beyond the ability of local resources to handle, each municipality needs a clear chain of requests, which could include federal or military resources.

a. During the workshops, execution events, and postevent discussions, it became clear that there was a semantic divide between local-level emergency responders and federal resource providers. DSCA and DSCIR are established processes, but they are not designed to facilitate municipal resource requests. Even requests made through the state government can be difficult to navigate. One federal representative from an organization responsible for coordinating DSCIR requests opined during a workshop that the discussion about DSCIR was irrelevant for JV because municipalities are not part of the process.

b. If DSCIR is indeed inappropriate for municipalities’ requests for support, then there should be an alternative avenue for requesting response actions in a controlled manner. JV has shown that national-level interests can be disrupted via local municipality and private company cyber compromises and exploitation.

- 4. The mechanisms and request chain for the military to request support from their surrounding community (“reverse DSCIR”) need to be explored.

a. In our force projection scenario, the critical infrastructure disruptions took place within the civilian critical infrastructure between the fort and the port. The communication between the deploying forces and the communities they passed through, which was very limited, focused primarily on law enforcement for traffic management purposes.

b. Though the findings above discuss DSCIR, there may be instances that require the military to request assistance from civilian agencies to resolve technical challenges. Though there are some critical infrastructure facilities located on military posts, installations rely on external forces for the bulk of their critical infrastructure needs.

- c. United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) and U.S. Army North should explore the possibility of the military requesting civilian assistance with critical infrastructure disruptions that take place outside of an installation but affect military operations within an installation or during movement in the case of force projection.

6.5. Support the Development of an Adaptable and Repeatable Framework

As codified in each JV iteration’s research objectives, the prevailing intent has been to develop a JV framework that would allow for this work to be duplicated and scaled. The ACI is a small think tank, and the teams that have developed and planned each JV have been composed of as little as two and as many as six ACI personnel. Though each exercise iteration of the JV research project is comprehensive and provides useful findings, the resource demands and 12- to 24-month planning cycle limit the number of events. Therefore, being responsible for planning and developing these exercises ad infinitum is not sustainable, even with corporate partners supplying additional manpower and resources. The rapid duplication and scaling of JV require a combination of automation and localization that empowers municipalities to plan and execute their own JV-like exercises.

6.5.1. Findings

- 1. Every municipality is different, so it is difficult to develop a “one size fits all” framework.

a. Though New York City (NYC) and Houston are first and fourth in population size within the United States, respectively, Savannah and Charleston are far smaller, ranking at 182 and 200, respectively.27 However, Savannah and Charleston are among the port cities through which Army assets deploy overseas and, as such, are strategically important for scenarios requiring force projection from the East Coast. The five locations that participated in the half-day mini-JV exercises support the full spectrum of military service branches, except the United States Space Force.

b. Within these municipalities are different commercial critical infrastructure organizations with varying relationships with respective their local governments. For example, the ports that the ACI has explored run the gamut from state-owned to partially state-owned to private enterprise. Rigid expectations for local relationships and governance structures would make scaling JV to fit municipalities’ needs and circumstances more difficult.

c. Additionally, because the JV approach is bottom-up, determining municipalities’ research and training objectives requires input from the municipality and its associated critical infrastructure organizations. For example, had Charleston and Savannah conducted the same scenario as NYC did in JV 1.0, the exercises would not have fit the cities’ needs and circumstances and would not have helped them prepare for a realistic cyberattack scenario in the region.

d. The DHS Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) also recognized this challenge and developed the CISA Tabletop Exercise Package.28 The package provides templates for documents required to conduct exercises as well as handbooks to conduct them based on affiliations, such as emergency services and government facilities.

- 2. The Law and Policy TTX is an integral part of the framework requirements due to the challenge of translating national-level laws and policies at the local level and differences in laws and policies across states and localities.

- a. JV 3.0 was the first exercise that spanned two different states, and there were significant differences in the governance structures between the states and the municipalities within those states. Additionally, there are multiple municipalities in both greater metropolitan areas that can play a role in responding to or remediating the effects of malicious cyber aggression.

27 City and Town Population Totals: 2010–2019,” United States Census Bureau (website), last updated May 7, 2020, https://www.census. gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-cities-and-towns.html.

28 “CISA Tabletop Exercise Package,” Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (website), n.d., https://www.cisa.gov/publication/cisa-tabletop-exercise-package.

b. Each organization and participant may be at a different level of cyber maturity and understanding. The Law and Policy TTX was an opportunity to ensure that everyone had a baseline of information on the local area’s governance structure, state agencies that address cyber issues and their processes, as well as what should be included in any organizational cyber response plan.

c. Additionally, the JV 3.0 Law and Policy TTX focused on the procedures for DSCA and DSCIR from a federal perspective. Although DSCA procedures and options are mature and have been exercised by states during natural disasters, DSCIR procedures had not yet been exercised at the time of the Law and Policy TTX in February 2020.

- 3. Municipalities do not have the dedicated staff to develop these events internally and will need low- to no-cost assistance to do so.

a. Although municipalities are experiencing more and more direct malicious cyber aggression, such as the recent cyberattacks in Texas, Atlanta, and Baltimore, most resources are held at the state level.29 Discovering cyber incidents is challenging, with 53 percent of successful cyberattacks going undetected until organizations are notified by an outside party. In addition, it takes an average of 197 days to identify breaches and an average of 69 days to contain them.30

b. As of July 31, 2019, there were 19,502 incorporated cities, towns, and villages in the United States, of which 3,092 had a population of 10,000 or more.31 In 4 years, the ACI has done full JV exercises in four of those places. DHS CISA also conducts critical infrastructure TTXs annually, reaching more locations than the ACI. DHS, CISA, and the ACI are low-to-medium cost options, with the main constraint being availability.

- c. Based on each of the JV iterations as well as feedback from the JV 2.5 workshops, it was evident that state entities had a better understanding of how to plan and execute cyber exercises. When counties or cities seek to conduct an exercise, they place the responsibility of planning them on their IT departments, which tend to be very small. Even if municipalities do use other departments, such as emergency services, they are usually very small, and they may not be familiar with cyber exercise planning.

6.6. Recommendations

Based on the insights and findings from the JV 3.0 exercise, the following recommendations address ways in which organizations could improve cyber resiliency. Although the recommendations include proposed lead organizations, they are only recommendations and do not take into consideration potentially conflicting missions and resources.

6.6.1. Municipalities should consider adopting new internal incident command structures that enable the formation of tailored whole-of-community efforts consisting of synchronized communication, information sharing, and resource allocation during cyber and emergency incident response.

29 Kate Fazzini, “Alarm in Texas as 23 Towns Hit by ‘Coordinated’ Ransomware Attack,” CNBC, updated August 20, 2019, https://www. cnbc.com/2019/08/19/alarm-in-texas-as-23-towns-hit-by-coordinated-ransomware-attack.html; Stephen Deere, “Feds: Iranians Led Cyberattack against Atlanta, Other U.S. Entities,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, November 29, 2018, https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/feds-iranians-led-cyberattack-against-atlanta-other-entities/xrLAyAwDroBvVGhp9bODyO/; and Emily Sullivan, “Ransomware Cyberattacks Knock Baltimore’s City Services Offline,” National Public Radio, May 21, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/05/21/725118702/ransomware-cyberattacks-on-baltimore-put-city-services-offline.

30 “Cost of a Data Breach Report 2020,” IBM (website), n.d., https://www.ibm.com/security/data-breach.

31 Erin Duffin, “Number of Cities, Towns and Villages (Incorporated Places) in the United States in 2019, by Population Size,” Statista (website), June 2, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/241695/number-of-us-cities-towns-villages-by-population-size/.

In conjunction with public and private sector partners, municipalities should explore the adoption of new, agile command structures for cyber incident response that are uniquely adaptable to local community needs. Events like JV can help municipalities identify existing and new pathways for adopting or adapting these structures to best fit their environments. The International Society of Automation Global Cybersecurity Alliance’s cyber incident response structure currently in development is just one example of such newly emerging approaches that introduce various integrated roles and a synchronized command structure.32 Although it focuses primarily on industrial control systems, this concept proposes an adaptable cyber incident command configuration that offers a model for further exploration. Accordingly, municipalities should not only explore such emerging efforts, but also actively seek to inform their creation. Doing so will help ensure these new frameworks possess a necessary agility that lends itself to effectively supporting local community resilience during cascading cyber incidents.

6.6.2. Establish a mentorship program between municipalities that encourages information sharing and joint cybersecurity exercises. The partnership program provides a safe learning environment in which local organizations can further develop their working relationships.

There is a broad spectrum of cybersecurity organization and maturity across the United States. DHS CISA is in the best position to create a mentorship program that could pair similar cities, counties, school districts, and military posts/camps/stations based on population, industry, etc., and their assessed cybersecurity posture. This partnership program would provide a safe venue in which smaller organizations and governments could learn best practices for cybersecurity, cyber incident response, and information sharing and coordination. Furthermore, the program would facilitate the development of cyber resilience from the bottom up and provide an ideal venue in which state and federal entities could evaluate the effectiveness of policies and procedures.

6.6.3. Federal, state, and local leaders must recognize cybersecurity and cyber incident response as a key responsibility and allocate resources to personnel, training, and education shortfalls accordingly.

The participants who had a higher degree of confidence and competence in cybersecurity, whether it was from prior real-world experience or training, rapidly oriented themselves to the cyber-focused scenario injects; quickly became attuned to their potential impacts; and began the decision-making process in support of incident response, mitigation, and remediation. Given the rapid evolution of the cyber domain, which includes the complexities of operational technology (OT) / IT integration, there is a critical need for including cybersecurity experts as part of both IT departments and foundational security programs for every sector and level of government. Leaders must understand that IT and information security are related but distinct disciplines, and then resource organizational staffing and responsibilities accordingly. Despite the shortage of cybersecurity professionals, organizations should continue to formalize and refine response plans in addition to resourcing training programs and conducting exercises to help close the gap.33 Furthermore, entities such as DHS and state-level cyber responders can assist by providing standardized, accessible, and relevant tools for city governments that may not have the time, capability, or resources to provide adequate cybersecurity. Where plans rely on requests for additional support, the thresholds for requesting support should be identified in advance and the procedures for requesting support rehearsed regularly. Only through experience, training, and preparation can we successfully respond to current threats while building future generations of responders.

32“Incident Command System for Industrial Control Systems,” S4xEvents (website), n.d., https://s4xevents.com/ics4ics/.

33 Steve Durbin, “10 Benefits of Running Cybersecurity Exercises,” Dark Reading, December 28, 2020, https://www.darkreading.com/operations/10-benefits-of-running-cybersecurity-exercises/a/d-id/1339709.

6.6.4 State cyber and emergency incident response entities, such as the SC Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity (SC CIC) program within SLED and the Georgia Emergency Management and Homeland Security Agency (GEMA), should work to establish standing, mutually supportive cyber resource support agreements that utiltize the Emergency Management Assistance Compact framework and Mission Ready Packages to build regionally focused cyber incident response and support plans for responding to a cascading cyber incident.34

JV 3.0 highlighted the potential value of creating cyber-focused memoranda of understanding (MOUs) within states and Emergency Management Assistance Compacts between neighboring states that can be utilized during significant cyber incidents, thereby providing critical cyber personnel, resources, and capabilities that already reside in the affected region. For example, SC CIC maintains MOUs with close to 100 organizations throughout the state that allow the 125th Cyber Protection Battalion, South Carolina (SC) National Guard—a member of SC CIC—to conduct on-site incident response with the consent of the governor. For regional, cyber-focused Emergency Management Assistance Compacts, the design must remain a state-led effort to ensure the proper tailoring of support packages that can adequately account for the unique characteristics of each state. These support packages should be formalized to include standing, tailored, regional cyber response Mission Ready Packages that can increase the speed, agility, and capability of support while ensuring the transparency of requirements and cost.35 The DoD and DHS should help foster and support these efforts: The DoD should do so through defense coordinating elements (DCEs), and DHS should do so through the Federal Emergency Management Agency and DHS CISA. Ensuring federal stakeholder presence can support additional meaningful facilitation and dialogue regarding resource sharing, gaps, and concerns. Additionally, having federal stakeholder support will also help bridge the gap between federal, state, and municipal cyber incident response efforts.

6.6.5. Federal and state entities should execute annual law and policy TTXs that extend to municipalities and private industry. These events provide a venue in which leaders and responders can identify gaps in authorities, rehearse resource requests, and identify potential thresholds. In particular, State and National Guard response authorities and mechanisms differ by state and locality, and these will continue to evolve as cyberspace is better understood. As such, the law and policy TTXs will be critical for understanding the roles and responsibilities associated with utilizing National Guard resources.

The law and policy TTX ensures all participants have a common understanding of the legal and political frameworks in which they are operating as well as an opportunity to review internal organizational policies and procedures prior to the exercise. Though it has been included in each iteration of JV to ensure participants have a baseline of knowledge, leaders and responders at all levels should adopt the event to improve expertise on response authorities and requesting resources. Furthermore, these types of TTXs are important for exploring the DSCIR process, which remains a relatively novel process that is not regularly executed nor exercised. It is recommended that these exercises be executed in conjunction with training on applicable laws in the area, existing policy documents, and historical cyber responses.

34 “Emergency Management Assistance Compact,” Federal Emergency Management Agency (website), n.d., https://www.fema.gov/pdf/ emergency/nrf/EMACoverviewForNRF.pdf.

35 National Emergency Management Association, “Mission Ready Packages,” Emergency Management Assistance Compact (website), n.d., https://www.emacweb.org/index.php/mission-ready-packages.

6.6.6. Federal and state agencies should design and establish a data repository for resources and data related to cyber incidents, tailored responses, impacts, and exercises to facilitate the sharing of policies, procedures, best practices, data, and emerging issues. The repository should be open for municipalities and private entities to deposit and utilize resources to increase the resilience of their associated critical infrastructure.

Events like JV exercises generate a lot of information, including policy information, best practices, and raw data. If available to verified users at the city, state, and federal level, access to and analysis of this data would prove useful in assessing cybersecurity programs and resource allocation. State and federal agencies would facilitate critical infrastructure research and resiliency by establishing a single repository for securely storing this data. Properly anonymized, this data would allow agencies to study trends in their areas of responsibility. An example of this initiative is SC CIC’s Cyber Posture Review, an assessment of critical infrastructure entities’ cybersecurity posture. The Cyber Posture Review collects and analyzes anonymized data to evaluate the overall cyber posture of the state. Cities and municipalities would benefit from this single certified repository because it would contain reliable resources and tools for assisting in the assessment, development, and improvement of the organizations’ cyber resilience.

6.6.7. DHS, in concert with the DoD, should examine and potentially expand the United States Coast Guard Cyber Command’s (CGCYBER’s) authorizations, resources, and mission set to include initial cyber incident response support for strategic ports and port cities.

With CGCYBER focused on defending its portion of the DoD Information Network, protecting the maritime transportation sector, and further enabling cyber operations,36 the DoD should examine provisioning additional resources to further develop the relationship and grow the number of trained, resourced, and readily available CGCYBER Cyber Protection Teams that can provide incident response support to strategic ports and local municipalities. USCG maintains several unique authorities, such as Title 14 (Coast Guard), Title 40 (law enforcement under DHS), Title 10 (warfighting under the DoD), Title 50 (intelligence), and Title 33 (“captain of the port”) authorities that enable speed, agility, and flexibility when coordinating not only a whole-of-government response, but also a whole-of-community approach through incident diagnoses, information sharing, and remediation efforts.37 USCG is uniquely positioned to help spearhead immediate response actions at strategic port locations in support of domestic critical infrastructure resilience and Army force projection operations. USCG cyber capabilities remain fully interoperable with both the DoD and DHS in support of homeland defense efforts;38 indeed, a standing cybersecurity and cyberspace operations memorandum of agreement already exists pursuant to Title 10 and Title 6 authorities.39 Additionally, as an active member of the Maritime Transportation System Information Sharing and Analysis Center, USCG maintains robust local and industry partnerships that will further facilitate a whole-of-community response.40 Accordingly, DHS, as the lead agency, should work with other supporting agencies, such as the DoD, in examining how allocating additional resources (funding, training,

36 Kimberly Underwood, “The Coast Guard Jumps into the Cyber Sea,” SIGNAL, February 1, 2019, https://www.afcea.org/content/coast-guard-jumps-cyber-sea.

37 Underwood, “The Coast Guard Jumps.”

38 J. R. Wilson, “CGCYBER and Coast Guard Cybersecurity.” Defense Media Network, March 14, 2018, https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/coast-guard-cybersecurity/.

39 Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Homeland Security, Memorandum of Agreement between the Department of Defense and the Department of Homeland Security Regarding Department of Defense and U.S. Coast Guard Cooperation on Cybersecurity and Cyberspace Operations (Washington, DC: DoD and Department of Homeland Security, 2017).

40 “MTS-ISAC Services,” Maritime Transportation System ISAC (website), n.d., https://www.mtsisac.org/services, accessed January 11, 2021.

and authorities), personnel authorizations, and capabilities can help expand CGCYBER’s mission scope to include cyber incident response and resilience efforts at strategic ports of embarkation.

6.6.8. Through the respective garrisons, U.S. Army Installation Management Command should work to develop, incorporate, resource, and exercise a tailored cyber incident response annex within its emergency incident response plans for force projection and deployment operations.

The Army has introduced a strategic framework that recognizes the ever-increasing likelihood that adversaries will target installations through cyber-enabled threat vectors.41 As this strategy continues to take shape, garrisons should synchronize and integrate resources, capabilities, and response protocols with municipal, state, federal, and private sector partners as appropriate. Garrisons should look for additional opportunities to embed, exchange, and cross-train personnel along with their municipal and private sector partners to build partnerships, shared understanding, and a common operating picture for responding to both physical and cyber incidents. It is also important that installations overseen by U.S. Army Installation Management Command have educated, knowledgeable, and trained resources who can recognize cyber activities that could be deliberate or system failures that impact day-to-day operations as well as force projection activities.

6.6.9. DoD planners must utilize integrated campaigning at multiple echelons (city, county, and state) to understand adversary actions against interorganizational partners and better inform campaign plan assumptions.

JV 3.0 provided a narrow glimpse into the impact that cyber incidents targeted at the city and county level can have national implications, particularly with respect to force projection. One can no longer assume freedom of movement in the current operating environment, and stakeholders will only gain a better appreciation of the impacts by studying commercial and interorganizational partners’ responses to and resilience against cyber incidents. The municipality focus of JV provides a structure that allows planners to understand how adversary actions impact these partners and subsequently inform the design and construction of campaign plans.

6.6.10. In conjunction with academic and government partners, the ACI should develop and implement automated tools that will allow novice planners to rapidly design and quickly execute JV-like events.

One of the critical goals of the JV series is to develop a repeatable and adaptable framework that reduces the time and difficulty involved with planning a cyber-incident response exercise. The ACI is producing static and generic guides, but these guides are a temporary solution because they do not provide a dynamic system that will tailor programs to a particular city or objective. The ACI is developing a suite of tools designed to automate the JV documents. Expected to achieve initial operating capability by March 30, 2021, the automated toolset includes a planner application that allows municipal and organizational planners to input, at a minimum, lists of their sector/subsector critical infrastructure, the length of their exercises, their exercise start dates, their difficulty levels (by sector), their locations, and the organizations that will be participating. The application will return a Master Scenario Event List (MSEL) for review and approval to the planner. Once finalized, the system will generate an Exercise Planning Guide, Player Handbook, and Data Collector Handbook for the planner to download as well as a file that can be imported into the Norwich University Applied Research Institute (NUARI) DECIDE® platform with the MSEL for conducting a TTX.

41 U.S. Army, Army Installations Strategy (Washington, DC: U.S. Army, December 2020), 1–22.

Table of Contents

- 1. FOREWORD

- 2. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- 3. INTRODUCTION - JACK VOLTAIC 3.0

- 4. JACK VOLTAIC RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

- 5. EXECUTION

- 6. FINDINGS

- 7. CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX A – ACRONYMS

- APPENDIX B – PARTNERS

- APPENDIX C – SCENARIO

- APPENDIX D – LAW/POLICY TABLETOP EXERCISE (TTX)

- APPENDIX E – LIVE-FIRE EXERCISE

- APPENDIX F – MILITARY TESTIMONIALS

- APPENDIX G – PRIVATE INDUSTRY TESTIMONIALS

- APPENDIX H – ALL HAZARDS ANALYSIS (AHA)

- APPENDIX I – CIRI FORT-TO-PORT DISRUPTION

- APPENDIX J – REQUIRED DELIVERY DATE (RDD) SIMULATION

- APPENDIX K – DSCA/DSCIR