Results

Final Studies Sample

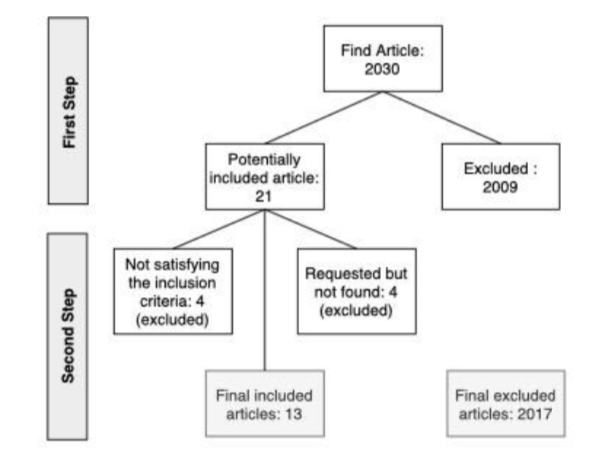

Figure 1. Flow Chart of the Study Selection Process

A total of 13 studies were identified for inclusion in the review after the aforementioned two-stage process. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the study selection process. In the article selection process, 13 empirical studies were retained, of which 9 were qualitative, 3 quantitative and 1 mixed method. Most are based on adults (n = 8), 3 young adult studies, and only two include both young adults and adults. All the studies include a female sample (n = 12), while only 1 study includes a sample with women (n = 44) and also men (n = 15) and 2 transgender women (n = 2). For these reasons, it was not possible to consider men and women separately. In regard to nationality, 7 of the studies have an Asian sample (n = 3 Nepali, n = 3 Indian, n = 1 Filipino), 4 research studies have participants from United States, 1 study uses a sample consisting of Indians and Americans, and 1 performed via the web has a mixed sample (Australia, Cambodia, Canada, Germany, India, Lithuania, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, United States, United Kingdom, and Uganda).

With regard to the trafficking process, 6 studies concern national trafficking, for example, in the case of India (Vindhya & Dev, 2011), 4 deal with transnational trafficking, and 3 studies do not specify the direction of the migratory route. An examination on the type of prostitution revealed 7 studies involving indoor prostitution (n = 2 in controlled places typical of domestic sex trafficking, n = 4 in brothels, n = 1 in brothels and/or private clients), 1 study concerning outdoor prostitution (street-based prostitution), and 1 study dealing with a mixed sample in which prostitution was performed indoor by Indians (brothels, dance bars, lodge-based prostitution) and outdoor by Americans (street prostitution). Out of the 13 selected articles, 4 do not specify the form of prostitution.

Content Results

The following paragraphs present the results obtained from the systematic review. We present them divided by levels (individual, relational, and structural). In each section, the factors are then organized with respect to the role they play in the exit path (hindering, facilitating, or controversial factors).

Individual Level

Facilitating Factors: Spirituality helps to provide a sense of hope and motivation to get out of exploitation (Hickle, 2017) as well as having life plans, and career projects for the future (Gonzalez, Spencer & Stith, 2017). During the process of regaining one’s autonomy, selfconfidence and self-esteem, the strengthening of a sense of self-efficacy and of feeling that one possesses the skills to satisfy one’s own needs encourages the victims to complete the path of emancipation from exploitation (Hickle, 2017). Furthermore, the desire to help others out of trafficking, by making their skills available to other people, is a stimulus to take life back in one’s own hands, giving it a meaning (Sukach, Castañeda & Pickens, 2018). In a study that compares a sample of exploited American and Indian women, the type of exploitation can affect the readiness to exit; specifically, in the Western sample, having had an experience of indoor (and not outdoor) prostitution is an element which helps victims abandon forced prostitution quickly (Wilson & Nochajski, 2016).

Hindering Factors: Two research studies (one on a Nepalese sample of trafficked women in brothels and one based on the collection of 15 testimonies of victims from different parts of the world) showed that the feelings of shame and uselessness due to being a victim of sex trafficking make it difficult to complete the exit path (Sukach, Castañeda & Pickens, 2018; Dalla & Kreimer, 2017).

Controversial Factors: Being addicted to substances (drugs/alcohol) is an ambiguous element. According to a study on domestic sex trafficking, having drug addiction problems hinders the recovery process, facilitating relapse and the return to prostitution (Gonzalez, Spencer & Stith, 2017). In another cross-cultural research study, however, having problems with substance abuse can increase/strengthen the drive for change (Wilson & Nochajski, 2016)

Relational Level

Facilitating Factors: Social support is positively associated with the exit process (Wilson & Nochajski, 2016). In particular, it emerges how the girls manage to escape exploitation thanks to the help of their companions; in fact, they rarely manage to break free on their own or through the intervention of the police who stage raids in strategic places with the intention of seizing the victims of sex trafficking (Dalla & Kreimer, 2017). One study also showed that customers helped women out of the street or pointed to the presence of “kidnappers” who helped women out of prostitution due to age, financial debt, or health conditions (Dahal, Joshi & Swahnberg, 2015).

Social support was also useful in the recovery process; the presence of mentors, professionals, roommates or positive leaders in reception/recovery facilities and friends outside the center (when present) are a resource in achieving emancipation (Gonzalez, Spencer & Stith, 2017).

Once out of exploitation, interpersonal relationships (with the staff of the host houses, lawyers, health workers) facilitate the holding capacity in the “new life”, containing the risk of returning to the street. Among the significant relationships, those who serve as the “peer mentors” of care-taking services play a crucial role (O’Brien, 2018). Feeling “connected”, in contact with former co-workers or places of recovery, members of social organizations, and people who have come out of prostitution contributes to reducing feelings of isolation, shame, and stigma and provides women with the motivation to pursue their personal goals. The sense of connection also includes spirituality (Hickle, 2017). The presence of a formal and informal support network favors the ability to build hope and an emotional support system (Sukach, Castañeda & Pickens, 2018).

In some studies, it has emerged that having children is significant: the hope/desire to be reunited with them provides the motivation to complete the path of emancipation (Gonzalez, Spencer & Stith, 2017; Hicke, 2017).

Hindering Factors: The fear of being recognized as a prostitute (labeling and stigma) makes the possibility of social integration complex (Crawford & Kaufman, 2008; Dalla & Kreimer, 2017). Denial, social rejection, and the feeling of being seen as degraded and corrupted make it difficult for people to re-enter society. Women often change their residence as a strategy to “shelter” against the stigma and stereotypes associated with their former life, which can lead to their return to the prostitution circuit (Dahal, Joshi & Swahnberg, 2015). Only in one study involving an Indian and US sample suggests that, for the Indian sample, the stigma may represent an accelerating factor with respect to change (Wilson & Nochajski, 2016); not wanting to be recognized any longer as “prostitutes” leads to the search for help. A study that analyzes the micro-aggressions that victims of sex trafficking are subjected to showed that they are exposed to derogatory language and face difficulties in being accepted as equal citizens and treated equally by others (Dhungel, 2017). In addition, invisible forms of rejection or sexualized objectification towards women are implemented. In the same study, it appears that offensive behaviors and attitudes are put in place towards these subjects; they are considered to be ignorant and inferior, to be people who can never reenter society, have a family, or participate in religious rites and activities. People’s beliefs in the fact that victims of sex trafficking possess fewer skills and the underestimation of their emotions (invalidating behaviors) amplify the difficulties of achieving social inclusion. Microaggressions affect not only the women’s physical and psychological health, but also their sense of isolation (Dhungel, 2017).

The description of sexually exploited children as “poor, innocent victims” worsens their possibility to develop relationships of trust with the services. The boys perceive themselves as “strong” because they survived and being looked at as “helpless” creates a reaction of repulsion towards the services (Williams, 2010).

Controversial Factors: The family can be seen both as a factor that obstructs the exit from prostitution (dishonor for the family in having a relative who prostitutes) (Dalla & Kreimer, 2017) or as a facilitating element (Hickle, 2017) because it offers victims motivation and encouragement to undertake emancipatory paths, especially if children are present. The people who participate in the same religious organizations as the victims can also be beneficial in helping them escape situations of exploitation and fit into a new context. In some cases, however, they are perceived as institutions that do more harm than good. In any case, they are seen not as the only organizations in a society that can actively do something to counteract the phenomenon (O’ Brien, 2018).

Structural Level

Facilitating Factors: A study of 20 Nepalese women highlights how social awareness programs on sexual trafficking can decrease women’s stigma (Crawford & Kaufman, 2008). Moreover, group and individual programs of empowerment and rehabilitation implemented by social agencies (especially involving addiction and/or use of substances) facilitate the exit process through the promotion of a sense of security, responsibility, self-efficacy, and through the restoration of a life routine and the recovery of professional skills (Hickle, 2017). A study conducted on 163 women victims of sex trafficking shows how the presence of agencies and welfare services helps people get out of exploitation (Bincy & Nochajski, 2018), particularly if they favor access to the labor market. The possibility of having access to professional contexts favors the resumption of one’s life (Sukach, Castañeda, & Pickens, 2018). Another study involving 30 young adults and their families, through analyzing their financial diaries, observed that limited access to jobs represents a key barrier to achieving financial stability for themselves, their children, parents, and other family members (Cordisco Tsai, 2017). The difficulty of finding a job, in fact, affects the possibility of having access to the control of household finances, of redistributing income to family members (parents), and of evading violent relations (Cordisco Tsai, 2017).

A study conducted with 30 Nepalese youths and adults has highlighted how NGOs, although helpful when it comes to immediate relief, are seen negatively because they do not prepare people to acquire the necessary skills for professional integration (Dahal, Joshi & Swahnberg, 2015). This lack of skills may result in an increased difficulty in reentering everyday life, especially due to the stigma and lack of social support that the people likely must face.

Even the presence of a security system can facilitate exit from trafficking: among those selected, a Nepalese study highlights how sometimes police raids allow women to escape exploitation; few people manage to escape autonomously because of age, health, or debts (Dahal, Joshi & Swahnberg, 2015).

As far as the cultural system is concerned, only one of the surveyed studies took this variable into account in the process of exiting trafficking. The work takes into consideration Indian and American girls; having a collectivist cultural orientation (in the Indian and American sample) and an individual one (in the Indian sample) can facilitate readiness for change (Wilson & Nochajski, 2016).

Hindering Factors: Low starting economic conditions make it difficult to escape prostitution (Bincy & Nochajski, 2018). Having little income even in the process of taking charge empowerment increases the chances of dropouts from the exiting process and the relapse into prostitution (Gonzalez, Spencer & Stith, 2017). Even low levels of cultural capital make it difficult to leave the exploitation circuit (Dalla & Kreimer, 2017).

Controversial Factors: No studies have been found in this section.